HANGIN’ WITH JUDGE HOFFMAN: My personal experience with the judge who presided over the trial of the Chicago 7

Aaron Sorkin’s new film, “The Trial of the Chicago 7,” focuses on the 1969 trial presided over by U.S. District Judge Julius J. Hoffman, along with the events that preceded it. The film, which is being released right now, has already earned 92 percent approval of critics on the website Rotten Tomatoes.

I served as a law clerk to Judge Hoffman during the two years before the trial began, and I could foresee much of what would happen in his courtroom. I later sat in on the trial, as a spectator, on two very cringe-worthy occasions.

In the film, Judge Hoffman is portrayed by Frank Langella, and a wide range of notable actors take the roles of the seven defendants, both well-known and more obscure. (The trial actually began with eight defendants; Hoffman severed Bobby Seale from the trial).

Here is an inside look at Judge Hoffman—what I observed during that frenetic time just before and during the trial.

* * *

In the fall of 1969, Judge Julius J. Hoffman moved from relative obscurity into the spotlight of national attention. Although he had earned a reputation within the Chicago legal community as an irascible judge with a strong conservative bent, he was otherwise a little-known figure. The public knew him only as one of Chicago’s U.S. district judges, and as such, he was generally respected. Besides, even lawyers who had appeared before him were compelled to admit that, despite his personal shortcomings, he could sometimes be an excellent judge.

All that changed in the fall of 1969. Assigned to be the presiding judge in what became known as the “Chicago 7” trial, Hoffman was suddenly the focus of journalists and lawyers from every corner of the United States, even the world. Suddenly his courtroom demeanor was under a microscope, probed for rationality and fairness. And just as suddenly, he became a national villain, even a national joke.

* * * * *

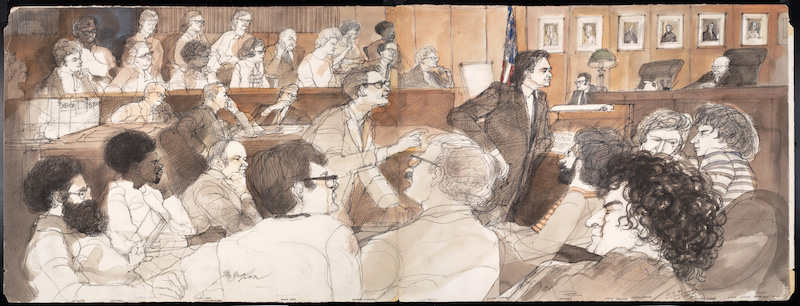

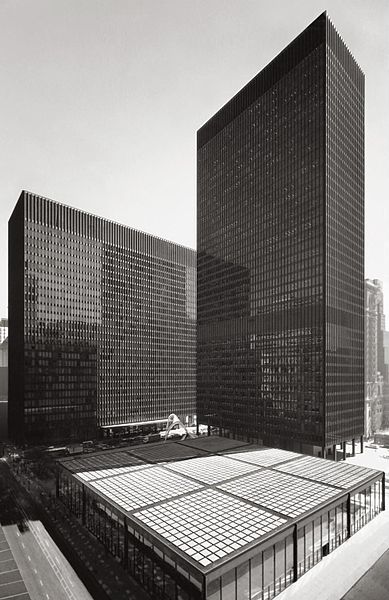

In his custom-made elevator shoes and his black robe (double-stitched for longer wear), Judge Julius J. Hoffman would stride imperiously into his courtroom. He would seat himself behind his imposing judicial bench, his tiny figure almost lost in the high-ceilinged courtroom he occupied on the 23rd floor of the federal courthouse in Chicago’s Loop.

Julius Hoffman was a diminutive, bald-headed man with a prickly ego that was easily punctured. But when I interviewed for a clerkship with him, he struck me as an altogether reasonable person to clerk for. I was in my last year of law school, and Hoffman was one of only three U.S. district judges in Chicago who had agreed, in that benighted era, to interview me, a woman, for the job of law clerk.

For a number of reasons, Hoffman became my first choice of the three, and when he offered me the job, I jumped at it. Although I had done almost no research into what kind of judge Hoffman was, I was thrilled with the simple prospect of being any federal judge’s law clerk.

My failure to research Hoffman’s reputation later came back to haunt me. I soon discovered that I was working for an irascible, difficult man who had unusual proclivities and a bizarre personality that often played itself out on the bench. So although I loved my job as a federal judge’s law clerk, and I learned a great deal from my experience, I was sometimes sorry I had so quickly settled on Hoffman as the federal judge to clerk for.

The “Chicago 7” Trial

In the spring of 1969, shortly before I was to finish my two-year clerkship, a new case arrived in Hoffman’s chambers. The case resulted from a grand jury’s investigation into the events that had transpired in Chicago the previous summer, just before and during the Democratic Convention in August 1968. Eight men, later described as the “Chicago 8,” were accused of violating a new federal law, the Anti-Riot Act, for inciting demonstrations and violent encounters with the police in the streets and parks of Chicago.

Countless books and articles have been written about the Chicago “conspiracy trial,” and I hesitate to further burden our electrical grid by focusing on it at any length. What I can offer is my unique point of view as someone who was working with Judge Hoffman at the very outset of the case, and who later–after the trial was over–discussed it with him briefly.

Anyone could see from the very beginning that this case was a hot potato–such a hot potato that it had already bounced around the courthouse a couple of times. Cases were supposed to be randomly assigned to judges according to a “wheel” in the clerk’s office. This time, however, the first two judges who’d been handed the case had sent it back. One of these judges was, according to rumor, the chief judge of the district court, William J. Campbell. I’m not sure about the other judge, but whoever he was, he had a lot more smarts than Hoffman did.

When the case landed in Hoffman’s chambers, he seemed somewhat taken aback, but I think he was secretly pleased to be handed such a notorious case. At first, he may have liked the idea that he would be handling a high-profile prosecution that would draw a lot of attention. In any event, his ego wouldn’t permit him to send the case back, even on a pretext.

I kept my distance from the “Chicago 8” case. As the senior clerk, due to leave shortly, I was not expected to do any work on it. My co-clerk was soon to be the senior clerk, and he therefore assumed responsibility for the pre-trial motions and other events related to the case. I was frankly delighted to have little or no responsibility for the case. It was clearly dynamite, and Hoffman was clearly the wrong judge for the case.

I could see what was going to happen long before the trial began. Counsel for the eight defendants (who later became seven when Bobby Seale’s case was severed, in a sadly shocking episode after the trial began) immediately began filing pre-trial motions that contested absolutely everything. As I recall, one motion asked Hoffman to recuse himself (withdraw as judge). The defense lawyers’ claim was that Hoffman’s conduct of previous trials showed that he could not conduct this trial fairly. If he’d been smart, he would have seized upon this motion as a legitimate way to extract himself from the case. But his pride wouldn’t allow him to admit that there was anything in his history that precluded him from conducting a fair trial.

Soon the national media began descending on the courtroom to report on Hoffman’s rulings on the pre-trial motions. One day Hoffman came into the clerks’ room to show us a published article in which a reporter had described the judge as having a “craggy” face. “What does ‘craggy’ mean?” he asked us. We were at a loss. The word “craggy” had always sounded rather rugged and manly to me, while Hoffman looked much more like the cartoon character Mr. Magoo.

I muttered something about “looking rugged,” while my co-clerk was too astounded by the question to say anything. Hoffman looked dubious about my response and continued to harp on the possible definition of “craggy” for another five or ten minutes, when he finally left.

The problem with Hoffman’s treatment of the “Chicago 7′ case was, fundamentally, that he treated it like every other criminal case he had ever handled. In other words, he was firmly biased in favor of the government prosecutors. He refused to see that this case was unique and had to be dealt with on its own terms, and he lacked the flexibility that might have helped the trial proceed more smoothly.

When the appellate court later reversed the defendants’ convictions, it noted Hoffman’s “deprecatory and often antagonistic attitude toward the defense,” and his comments that were “often touched with sarcasm.” It added: “Taken individually any one was not very significant and might be disregarded as a harmless attempt at humor. But cumulatively, they must have telegraphed to the jury the judge’s contempt for the defense.” In truth, each of the appellate court’s comments might well have applied to almost any criminal prosecution that took place in Hoffman’s courtroom, given the same length and intensity of this trial.

At the same time, it’s only fair to add that it was clear from the beginning that these particular defendants didn’t want to play the game the way defendants are supposed to. They were determined to upset the courtroom at every opportunity. So a lot of the blame for the fiasco that followed must therefore fall on their shoulders as well.

At the end of the trial, Hoffman convicted all seven defendants and two of their lawyers of contempt for their behavior during the trial. After these convictions were reversed and sent back for trial, a federal judge who was brought in from Maine found three of the defendants and one of the lawyers guilty of contempt.

The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals later upheld these convictions. (In re Dellinger, 502 F.2d 813 (7th Cir. 1974). It even acknowledged that these three defendants (Abby Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and David Dellinger) were guilty of serious misbehavior and “overwhelming misconduct,” including the wearing of judicial robes in court. It also upheld the conviction of defense attorney William Kuntsler, noting that his bitterness and anger on at least one occasion “constituted a vicious personal attack on the judge,” delaying and disrupting the trial.

We should also keep in mind that the conduct of the trial by the government prosecutors was harshly criticized by the appellate court. These lawyers, who represented the Nixon administration, took advantage of Hoffman’s general bias in favor of the government, encouraging him to rule in favor of the prosecution–as was his wont–regardless of the merits of its position.

My conclusion, when all is said and done? The government never should have brought the indictment in the first place. It was ill-conceived, and although the statute under which it was brought was later held by the Seventh Circuit to be constitutional, it was a highly dubious piece of legislation, spawned by the turmoil and the upheavals of its time. If the Nixon administration had not pursued the indictment, this whole sorry chapter in U.S. legal history would never have been written.

In the end, Hoffman’s reputation was besmirched as almost no other federal judge’s reputation has been, before or since. I observed the trial twice, and each time I was extremely uncomfortable. I was a lawyer with the Appellate and Test Case Division of the Chicago Legal Aid Bureau by that time, and highly embarrassed by Judge Hoffman’s behavior, I cut off my relationship with him almost completely.

When I decided to leave Chicago and move to California several months later, however, it seemed only right to phone the judge to tell him I was moving and to say goodbye. Over the telephone, I didn’t mention the trial, but after an awkward silence, he did. “I still don’t understand what happened,” he told me. He sounded mystified, hurt without understanding why–or perhaps, without wanting to understand why.

* * * * *

Would Judge Hoffman be viewed differently today? I can’t help wondering. In an era when sharp-tongued “Judge Judy” has one of the hottest shows on daytime television, the public appears to admire an acerbic judge more than one who displays what’s generally described as “judicial temperament.”

But as an erstwhile lawyer, and as a citizen concerned with our criminal justice system, I think that “Judge Julius”–so lacking in judicial temperament–was far from the kind of judge we need. Although a “Judge Judy” may be an amusing figure in the world of entertainment, lawyers and litigants in the real world deserve better.

With special thanks to the Chicago History Museum, a fascinating place to explore.

I really enjoyed your review and opinion of the trial and the judge. While I remember the trial and the crazy times in Chicago in 1968, I did not appreciate it from a legal standpoint. Your background and first hand experience made your explanations very real and vivid. I am looking forward to seeing the film now, and with “new eyes!” Thank you!